Wine Yeasts: Myths and Realities

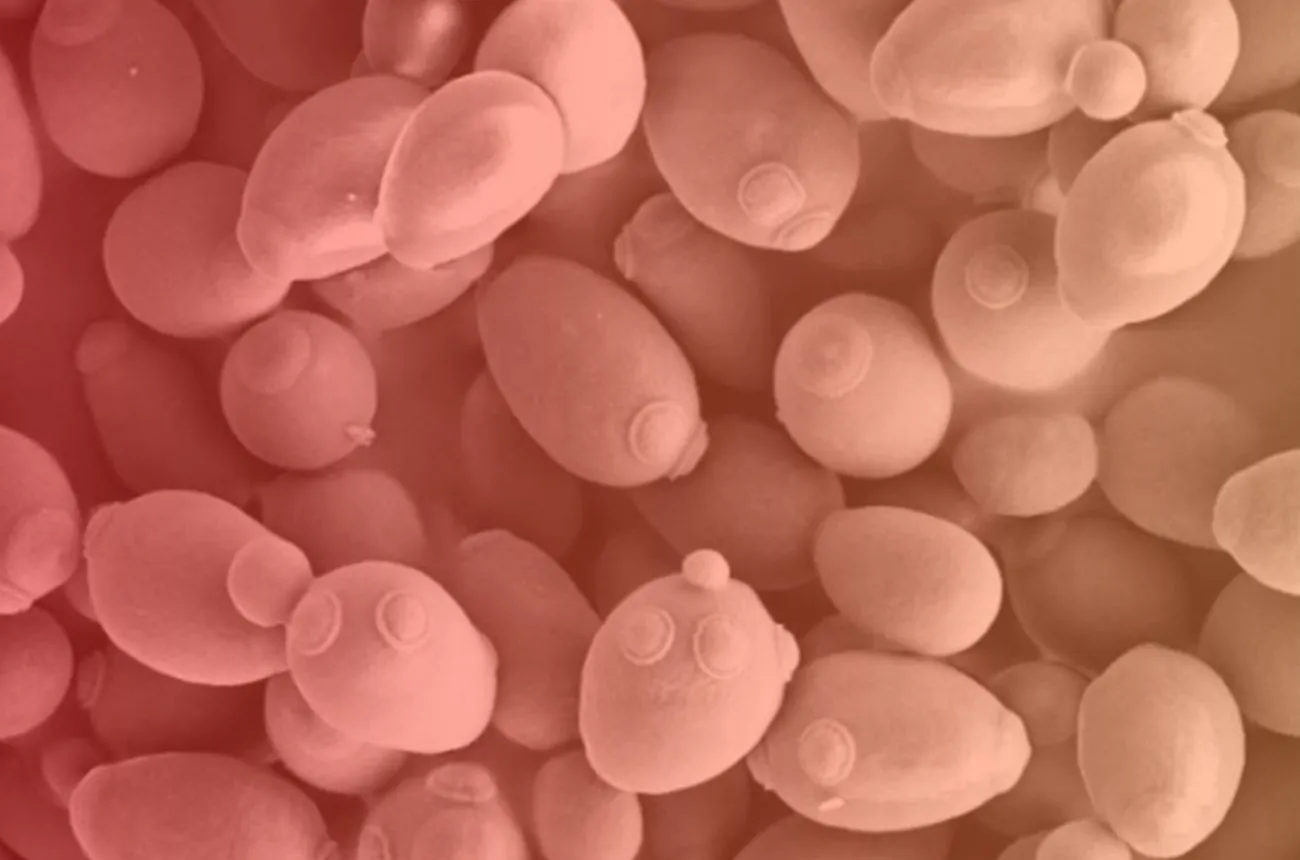

Yeasts are among the most fascinating yet misunderstood players in winemaking. Though invisible to the naked eye, they form a vibrant ecosystem on the skin of every grape, awakening at harvest and fully expressing themselves in the winery.

Far more than simple agents of fermentation, yeasts are the true architects of a wine’s identity — shaping not only its alcohol, but also its aromas, flavours, and textures.

In this article, we explore common myths about wine yeasts, their real functions, and why understanding them is essential for appreciating wine at its deepest level.

Myth 1: Yeasts Only Exist to Create Alcohol

It is true that yeasts are responsible for transforming grape must (freshly pressed juice) into wine through alcoholic fermentation. By converting grape sugars into alcohol and carbon dioxide, they make wine possible in the first place. Without yeasts, there would be no wine.

But their role goes far beyond alcohol production. Yeasts influence the entire sensory profile of wine:

- Aromas: Different yeast strains generate esters, thiols and terpenes, which give wines their floral, fruity or citrusy notes — think grapefruit, passionfruit, or orange blossom.

- Texture: By producing glycerol, yeasts add body and roundness. Through autolysis (their natural breakdown after fermentation), they release polysaccharides that soften tannins and increase perceived volume on the palate.

Modern winemaking also uses non-Saccharomyces yeasts alongside traditional strains. These can boost complexity, fine-tune acidity, and even lower alcohol levels. This makes them powerful tools for tackling climate change challenges (which threaten terroir expression) and for meeting new consumer preferences for lighter wines.

Myth 2: Selected Yeasts Are Artificial and Erase Terroir

A widespread romantic belief claims that only “wild” or spontaneous fermentation produces authentic wines. According to this view, inoculating must with selected yeasts is artificial and masks terroir.

In reality, spontaneous fermentation is a risky lottery. Vineyards and cellars host a mix of beneficial yeasts and harmful ones that can stall fermentation or create off-flavours. No winemaker can leave such crucial factors entirely to chance.

Selected yeasts are not an artificial intrusion but a careful curation. Winemakers may isolate and multiply strains from their own vineyard or region, ensuring consistent fermentations that respect tradition.

A classic example is the QA23 strain, isolated in Portugal’s Vinho Verde region. Rather than masking terroir, it highlights it: QA23 enables clean, precise fermentations that allow Alvarinho and Loureiro grapes to fully express their aromatic potential. Far from erasing regional identity, it shines a spotlight on it.

Myth 3: Authenticity Requires Spontaneous Fermentation

Some argue that great winemakers should surrender all control during fermentation. Yet Portugal’s most respected producers show the opposite: the choice between spontaneous or inoculated fermentation is not ideological, but technical.

Spontaneous fermentations can add character, but risk inconsistency.

Inoculated fermentations provide control, ensuring purity and consistency.

For leading winemakers, yeast is a tool of precision. Authenticity does not lie in blindly following one method, but in achieving wines that reflect their terroir faithfully and brilliantly.

Renowned winemaker Anselmo Mendes himself began his career by researching yeasts in the Vinho Verde region, long before releasing wines under his own name. His path shows that true authenticity comes from knowledge, vision, and mastery — not from dogma.

Yeasts as the Link Between Terroir and Winemaking

Yeasts should not be seen through false oppositions: science versus nature, or artifice versus authenticity. For thousands of years, they have been essential not only to wine, but also to bread, beer, cheese, and cured meats.

In winemaking, their role is both natural and timeless. Used wisely, they are the bridge between what the terroir provides and what human skill can achieve. At Quinta da Alameda, this is the philosophy behind our pure wines of the Dão: respecting the land while embracing knowledge to let it shine.

FAQs About Wine Yeasts

What are wine yeasts?

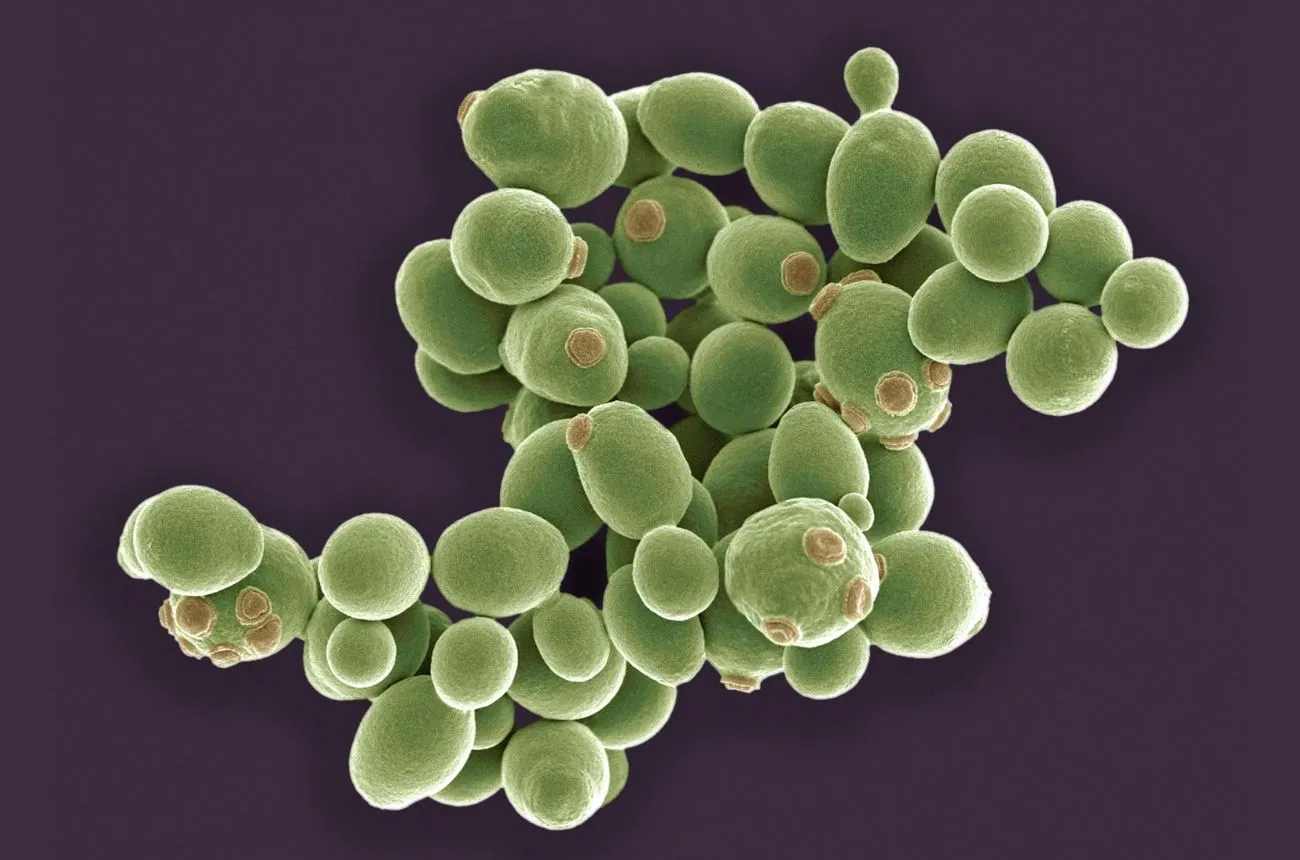

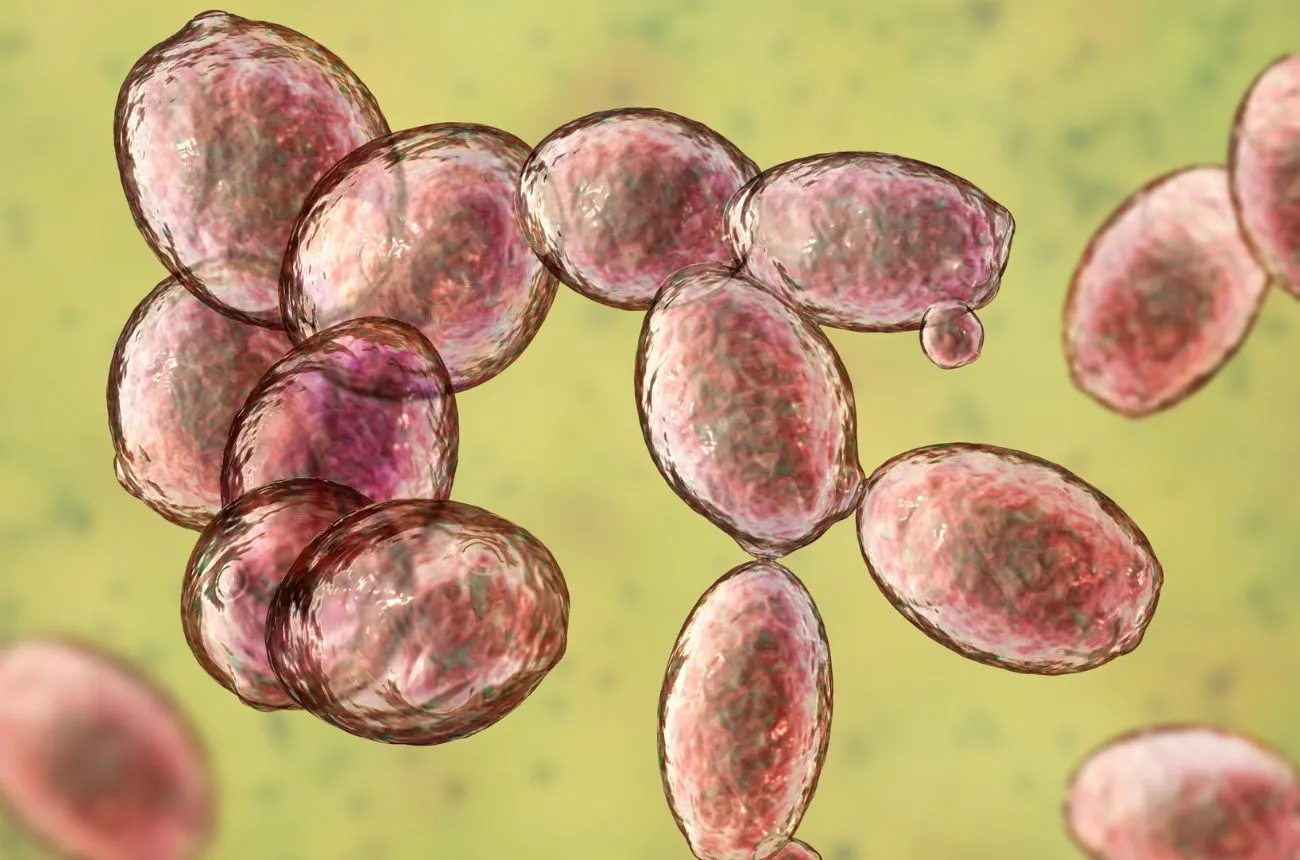

Wine yeasts are single-celled fungi, with Saccharomyces cerevisiae being the most important species. They transform grape sugars into alcohol and carbon dioxide through fermentation.

Do yeasts influence wine aromas and texture?

Yes. They produce compounds like esters and thiols that define a wine’s aromas, while also generating glycerol and polysaccharides that shape its texture, roundness, and creaminess.

What are non-Saccharomyces yeasts?

These are alternative species such as Lachancea thermotolerans or Torulaspora delbrueckii. When used in co-fermentation, they can adjust acidity, lower alcohol, and add complexity.

What’s the difference between spontaneous and inoculated fermentation?

Spontaneous: driven by native yeasts from the vineyard and cellar; variable results.

Inoculated: guided by a chosen strain; clean, consistent outcomes. Both are valid technical choices.

Do selected yeasts reduce authenticity?

Not when carefully chosen and locally sourced. In fact, they can enhance typicity while avoiding faults.

What is lees ageing (sur lie) and bâtonnage?

Keeping wine on fine lees (sur lie) or stirring them (bâtonnage) encourages the release of peptides and polysaccharides, enriching texture and complexity.

Are live yeasts or sediments a problem in bottled wine?

Not usually. Some unfiltered wines, pét-nats, or sparkling wines retain yeasts and natural deposits, which are safe. Still wines are often filtered to avoid them.

What is Brettanomyces?

A spoilage yeast that can create unwanted aromas like stable, leather, or adhesive. Controlled with strict hygiene and careful winemaking practices.

How does malolactic fermentation differ from alcoholic fermentation?

Alcoholic fermentation: carried out by yeasts, converting sugars into alcohol.

Malolactic fermentation: carried out by bacteria, softening acidity by converting malic acid into lactic acid.

Key Takeaway

Yeasts are not just the silent workers that turn juice into wine. They are natural, complex, and essential players that define how a wine smells, tastes, and feels. Whether spontaneous or selected, they remain the crucial link between terroir and winemaking — shaping wines that carry the signature of both the land and the winemaker’s vision.

Article reviewed by Patrícia Santos, head winemaker at Quinta da Alameda. She holds a degree in Oenology from UTAD (University of Trás-os-Montes and Alto Douro, 2001), and trained under the guidance of Anselmo Mendes. Her experience spans the wine regions of Dão, Bairrada, and Beira Interior, as well as Arribes.