Quinta da Alameda in the Vigneron Initiative: The Complete Authorship of Portuguese Wine

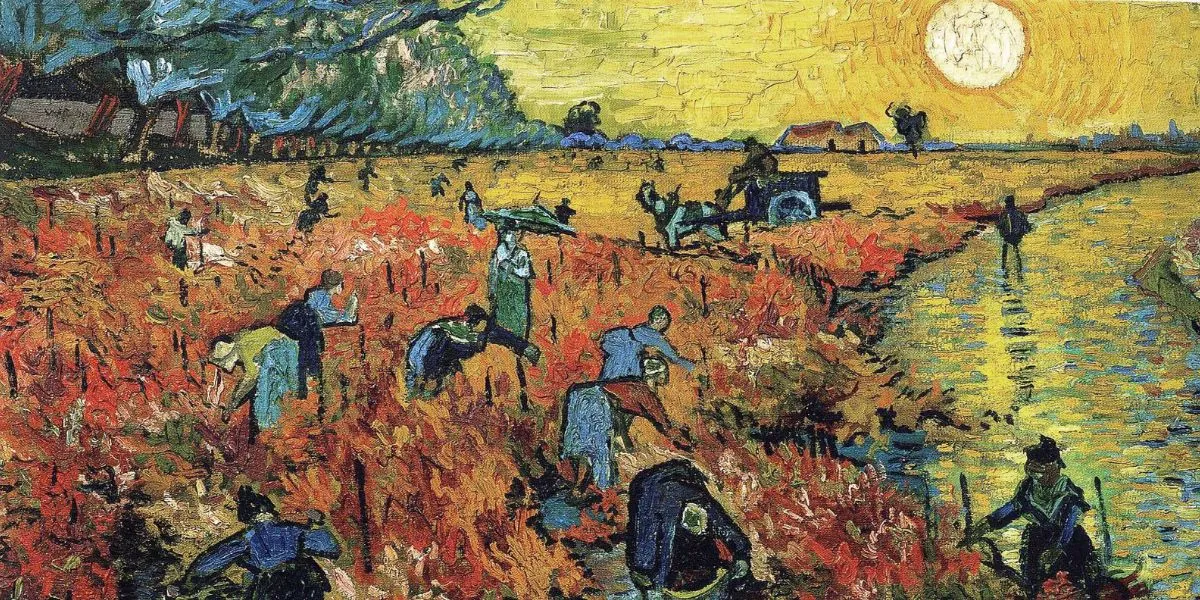

The letters Vincent van Gogh wrote to his brother Theo contained a line that surfaces throughout his correspondence: “Everything that is done with love is done well.” It is a simple affirmation that defends the idea that authenticity arises from emotional devotion and from the intimate bond between the author, the raw material and the finished creation.

Yet this sentiment is not unique to the Dutch painter. In the realm of art, in one form or another, almost every truly pioneering creator shares the same conviction. The same holds true for the art of winemaking. This is why Van Gogh’s maxim so accurately describes the essence of the Vigneron movement, an initiative led by a group of Portuguese winegrowers who joined forces to defend a more genuine, more integrated and more transparent model of wine production.

Integral Authorship: What Defines a Vigneron

This initiative is carried out by a small group of ten Portuguese producers, among whom Quinta da Alameda is included. As its French origin suggests, the term vigneron refers to someone who grows their own grapes, vinifies them in their own winery without resorting to fruit from elsewhere and bottles the wine produced from their own vineyards.

This establishes a clear distinction from producers who buy grapes from third parties, a very common practice in Portugal and beyond. At the same time, the initiative aims to highlight the direct, hands-on work of Portuguese vignerons throughout the entire winemaking cycle.

In Portugal, these producers are formally known as vitivinicultores-engarrafadores — a complex and not especially memorable term — and their activity is strictly regulated by the IVV, the public body that oversees and coordinates the national wine sector. Being a vigneron is therefore not a question of stylistic preference. It is a claim to full authorship, anchored in the spirit of the law.

A Movement Born of Real Challenges and Clear Ambitions

The initiative gained momentum during the event “Our Grapes, Our Wines”, held at Quinta das Bágeiras. The wide range of regions represented sought to show that being a vigneron does not depend on scale but on fidelity to the terroir. Indeed, contrary to common belief, a vigneron is not simply a small wine producer.

The strength of the movement has grown out of the challenges faced by vignerons across the country. Grape prices remain low. Retail exerts considerable pressure on wine pricing. Climate change brings uncertainty to each harvest. Traceability is often overlooked. Imported bulk wine distorts market values. Several regions struggle with excess stock. And consumers have largely lost the ability to distinguish those who grow their own grapes from those who merely buy them. The former prestige of “estate wine” has, to some extent, faded.

At the same time, today’s consumer seeks transparency, truthfulness and identity. The Vigneron model satisfies these expectations because it offers an exclusive origin and complete authorship without shortcuts.

Yet the obstacles are substantial. Being a vigneron demands significant costs, major investment and constant dedication. It requires educating consumers and intermediaries, protecting the term against misuse and converting the philosophy into sustained economic value. Still, if these hurdles are overcome, the initiative may foster innovation, safeguard unique traditions and restore dignity to Portuguese viticulture.

The Three Pillars that Sustain the Vigneron Philosophy

The aims of this initiative rest on three pillars. First, it seeks to guarantee the full authenticity of the wines. Secondly, it intends to ensure total quality control at every stage of production. Finally, it wishes to demonstrate the devotion, commitment and profound knowledge of each vigneron — because, as Van Gogh himself affirmed, only what is born of love for its subject can ever be truly well made.